My name is Marco, and I’ve been living with dementia for close to ten years now. It started with the little things — forgetting names, losing track of appointments, mixing up the order of everyday tasks. At first, I chalked it up to age. But my partner began gently pointing out things I hadn’t noticed. I was in my early seventies when it became too obvious to ignore.

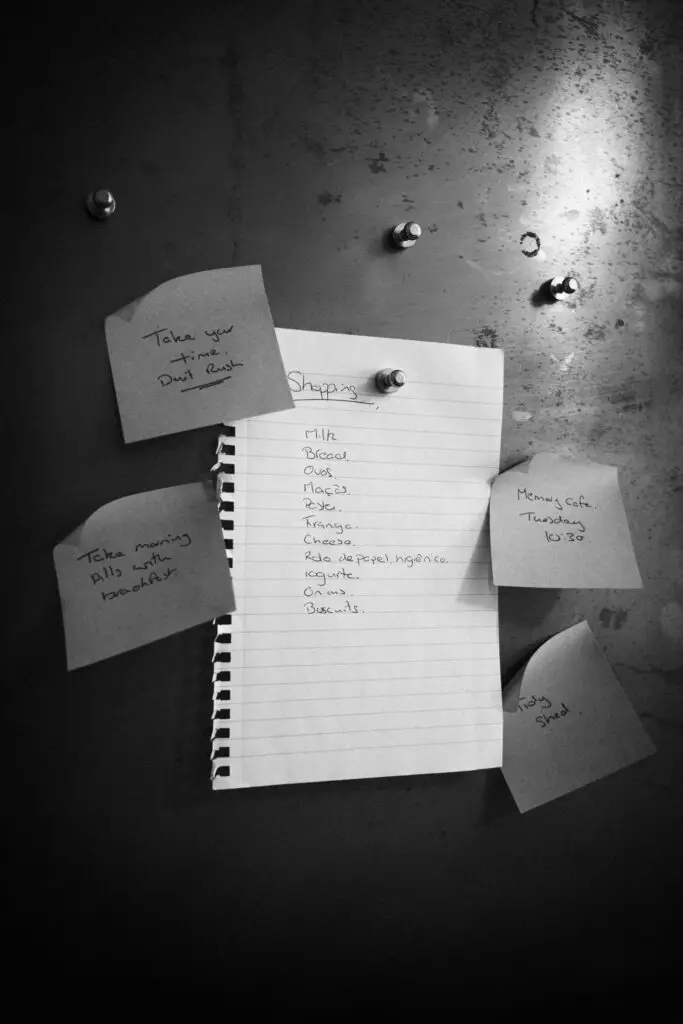

Eventually, I went to the GP. He referred me to a memory clinic, and not long after, I was diagnosed with mild dementia. That appointment is still clear in my mind. My partner sat beside me, holding my hand. We were both shaken. I started medication soon after — I still take it, though if I’m honest, I don’t know if it’s made a difference.

We moved to England in the mid-1980s from Braga, in northern Portugal. We settled in Hertfordshire, where we’ve lived ever since. It’s where we raised our three children — two sons and a daughter. I worked in the estates department at a local university, mainly in maintenance. I liked the practical side of the job — fixing things, solving problems. Before that, back home, I trained as a metalworker. After I retired, I went back to it a bit, making small pieces in the shed. It helped to keep my hands moving and my mind focused.

My family is everything to me. These days, I also help care for my wife, who hasn’t been well for some time. That’s harder now. Dementia gets in the way — I forget things, get distracted, sometimes even confused about what I was meant to be doing. That part frustrates me. I’ve always been someone who liked things done properly. I still keep up appearances — I’m particular about looking neat and tidy. That hasn’t changed.

Speaking is more difficult than it used to be. On the phone especially, I get stuck for words. And when I’m tired or anxious, I slip into Portuguese — especially when I can’t find the English. It just comes out. I’ve lived here for decades, but in those moments, it’s like I’ve gone home without meaning to.

The worst part is not knowing what I’ll forget next. I hate that feeling — of not being able to rely on my own mind. And the thing that scares me most is the thought that, one day, I might not recognise the people I love.

Still, I try to hold on to who I am. I’m a sociable person. I love a chat, a laugh. There’s a memory café nearby that I go to regularly — it’s something I look forward to. I wish more people understood what it’s like, though. Dementia isn’t just forgetting things. It’s losing confidence. It’s feeling like a burden. It’s work — hard work — just to keep going.

But I’m lucky. My family have been incredible. We’re close. We’ve always been close. I don’t see many old friends these days, but I never feel alone. We still do things together — watch TV, go shopping, cook dinner. I might lose track of the plot sometimes, but I still love being part of it all.

There are emotional days. Days when I feel the weight of it — especially when I can’t support my wife the way I used to. But we’re still a team. We talk, we laugh, we carry on. That hasn’t changed.

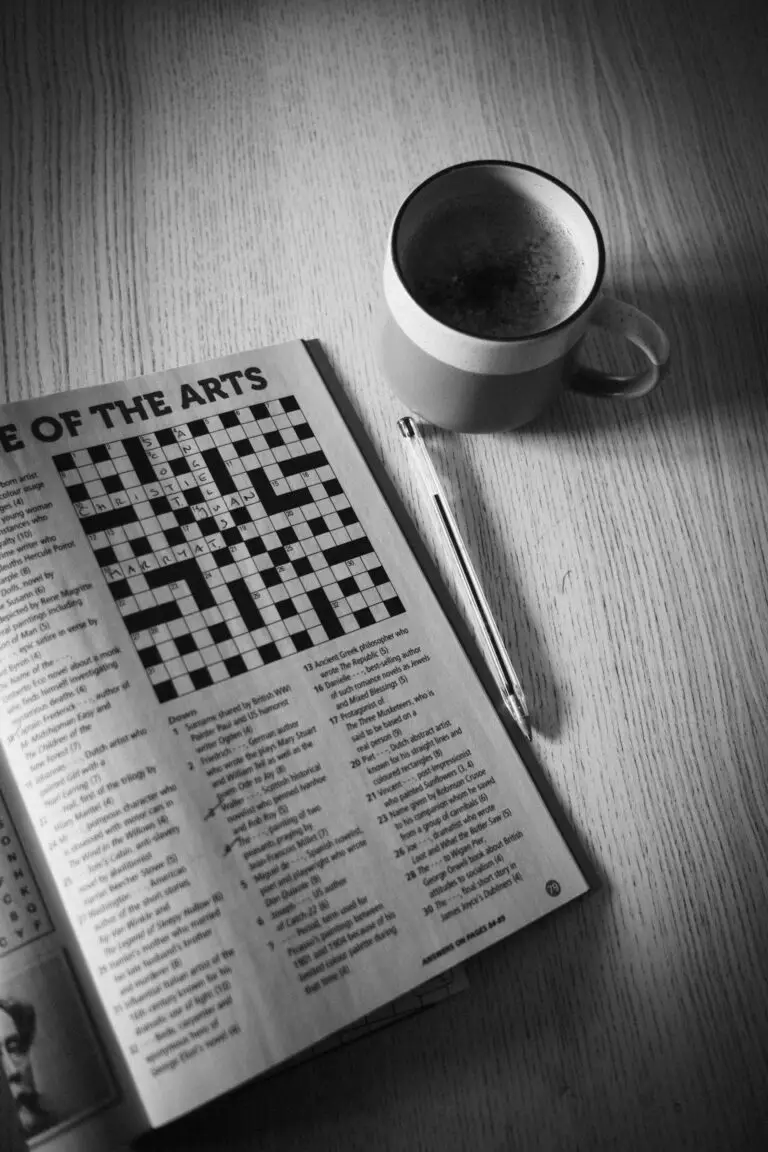

I find comfort in small things — gardening, listening to old Portuguese music, playing word games on my tablet. I still go to local coffee mornings, and in the early days, I was part of a great support group run through the hospital. I wish there were more things like that around now.

If I had one bit of advice, it would be this: don’t shut yourself away. Keep socialising. Keep talking. Be kind — to yourself, and to others. Even now, there’s joy in being included, in being seen.

I still hope that one day they’ll find better treatment. But in the meantime, the silver lining is this — my family has become even closer. And for me, that means everything.

If I could share just one message, it would be this:

“Keep showing up. Don’t disappear into it.”

There’s still so much living left to do.